Maurice Booth

Summary of WW2 loss of Lancaster, and life in a PoW Camp.- Account by Maurice Booth. 115 Squadron.

I was the navigator of a Lancaster hit in the anti-aircraft barrage over Berlin at about 2.30am on January 3rd 1944. The flak had seemed even more intense than usual that night, when with a deafening explosion the aircraft instantly dived out of control from 22,000 to . who knows?. Fortunately we had dropped our bombs. If we had still had on board the 4000lb bomb and hundreds of incendiaries, there would have been no hope. I

remember thinking, quite calmly, "I shall be dead in a few seconds." when the pilot and flight engineer using their combined strength managed to level out, amazingly, since the fact that both starboard engines were inoperative, one of which was immediately on fire, and the second soon left its trail of flame. Isolated from the main force, we soon found ourselves flying in an avenue of parachute flares, and Me110 night fighters were attacking us at will. With only port engines in use it was difficult to manoeuvre, and in spite of fire from our gunners, the Lancaster was soon mortally wounded, and both gunners were injured.

I knew then that there was no chance at all of getting home. Navigation was difficult with the aircraft flying at an angle because of all the pull being on one side. My chart was suddenly flooded with some fluid - glycol, I expect, and would not be usable. Anyway the fighters would soon finish us off. Knowing the situation we were in, our pilot and captain, Flight Sergeant Bob Hayes ordered us to bale out. While we did so in turn and in good order, he kept the aircraft on as level a course as he could manage until we were all out, but by the time he could leave, the Lancaster was too low, and crashed and Bob died. One of many who gave their lives to save their crews.

I dived out into the rain, and saw the flames pouring out of the two engines as the Lancaster roared away. My parachute opened, and I remember thinking that my mother would receive a telegram beginning, I am sorry to inform you.." It was too dark to see the ground coming up, and suddenly I was down in soft grass being dragged along by the wind. Even before I was rid of my parachute I heard voices shouting excitedly. I came down by a group of Germans who led me to a nearby hut, where I think they were in charge of charge of a barrage balloon site. In spite of the glow of Berlin on fire in the Eastern sky, they treated me well, gave me coffee, at least they called it coffee, and were concerned that I might be injured. The police who came to take me away told me that the body of a young airman had been found nearby with his parachute not fully opened. A friend of mine has recently discovered on the internet that Bob lived until the 26th of January. He is buried in the 1939 - 1945 War Cemetery in Berlin.

As to the crew members, the Wireless Operator, rear gunner and I went to Stalag 4B. The rear gunner was repatriated with injuries quite soon after arrival at the camp. From the Internet it seems that the mid upper gunner was also injured and repatriated. The Bomb Aimer, a Canadian and therefore a commissioned officer, as were all Canadian aircrew, and would therefore have gone to a different camp. The Flight Engineer was

recorded as having been at Dulag Luft but was not recorded at a PoW camp. So apart from the Pilot, Bob Hayes who was killed and the Wireless operator, "Taffy" Wardale, I know no more about the fate of any of the crew. What little I have has been passed to me by friend from the Internet.

I spent the night in Magdeburg Hospital, and when they found I was uninjured I was taken to Dulag Luft, the interrogation centre for captured airmen at Frankfurt on Maine. The German interrogating officer asked me where was the base from which I had flown. We had been told many times not to say more than name, rank and number, as those who start getting into conversation with the friendly enemy officer, are likely not to get to their PoW camp for much longer. I said, "Sir, as you know, I'm not able to tell you more than my name, rank and number." (Well, we had not

long before moved to Witchford in Cambridgeshire.) The officer said, Sergeant. There's no Witchcraft about it. and pointed to the map. I

laughed at his joke. I thought it wise!

A few days later, with many others, we travelled in closed but cold trucks for a three day journey, with many stops, to Stalag IVb at Muhlburg on Elbe, where I was to spend the next seventeen months. As soon as we were through the gates my spirits rose, as behind the wire I thought I recognized one or two faces of aircrew from my squadron who had failed to return from their operations and whom we supposed had been killed, yet here they were, seeming well and cheerful as we waved to one another.

Stalag IV B was the biggest PoW camp in Germany, receiving the first prisoners, Polish soldiers from the German invasion in September 1939. When the war ended there were about 30,000 prisoners, it seems, of every nationality which had fought against Germany. I have read that there were even some Italians towards the end of the war. The place was organised into "Compounds", each compound housing

prisoners speaking the same language or similar culture. In my hut, probably most were British, but there were also some Dutch, Poles, French, and some South Africans, and even some Danish Policemen and a few east European. Russians had their own compound and did all the dirty smelly work on the camp, Many died of malnutrition, tuberculosis, and typhus.

I found life there no worse than I expected. At least we were not maltreated by our guards, who no doubt kept to the Geneva Convention for the care of prisoners of war. Russia had not signed the convention, and the Russian prisoners did not receive Red Cross Parcels. In spite of regular "news" from the Germans telling us that the Allies were in full retreat, we knew that we would win the war. Our more immediate concerns were how to keep healthy and fit. One fear was of typhus, and any time one could see men sitting on their beds plucking out the little black spots of the typhus louse from the seams of their vests etc. The other thing that occupied our minds was "How will it end?" When the Red Army reached the Elbe, would we just be abandoned, or what? Of course we hoped that the Americans would arrive first from the west.

Our hut was quarantined twice because of typhus. Once was when the Americans were flying overhead to bomb Dresden after Bomber Command had bombed the night before. Of course, many of us pushed into the doorway to watch the planes go over. After a bit the guard, a soldier with a patch over one eye, home from the Russian Front, had had enough and got in front of the pushing prisoners, and started to prod anyone within reach, including myself, with the bayonet on his rifle. He just left a bruise, and to be honest, I felt sorry for him! To see all those huge bombers flying unopposed bombing a beautiful town which he would have thought not a military target, it was no wonder that he lost his cool. We understood that most of the guards had been fighting on the Russian Front, and were given the duty of guarding the PoW camps because of their injuries or their mental state made them unfit for combat duties. Anyway that was the only time I saw any "violence" from a German guard, and it really was excusable. Most of the time they didn't bother us apart from roll calls and enforcement of curfew etc.

I remember well when I was walking alone in the British compound, I realised it was strangely quiet because it was past curfew time, and I supposed I could be shot for breaking curfew rules, so I started to run and fell over a pile of frozen sand and gravel and tore back a mass of skin from the base of my right thumb. At home it would have had stitches, but all I could do was to run cold water over it and wrap it tight in a dirty handkerchief. In those unhygienic conditions I was sure it would become infected, but in fact it healed remarkably well. I can still just see traces of that injury.

It was amazing that living in such dirty, cold conditions, and in spite of the valuable Red Cross Parcels, on a very restricted diet, we, at least among my friends, there was no illness of any consequences that I can remember. The food supplied by the Germans was mainly "skilly". A collection

of all sorts of vegetables boiled up together and potatoes boiled in their skins. The Red Cross Parcels made such a difference to our diet, until they stopped coming after the second front because of transport problems from Allied bombing and advances in France and into Germany.

Beds were three tiered affairs, side by side in pairs and possibly end to end too; I can't remember. There was need to use the floor space as neatly as possible. Each bed had a "mattress", ie a bag filled with something that had compressed under the weight of numerous changes of occupant. There were no sheets, but one or two blankets. Underneath the mattress the sleeper rested on "bedboards", which were short lengths of plank across the bed resting on longitudinal runners on each side, You were very fortunate indeed if you had enough bedboards to support you properly all the way. Most beds had a couple or more gaps where an early occupant had lost a bedboard or even had it stolen or sold for cigarettes. the universal currency both among prisoners and for trade with the Germans.

It was every man's wish to live on a top bunk and I mean live, as if everybody was on the floor at once it made the place very crowded indeed, so a lot of social conversation took place on or by the beds. A top bunk meant you were not troubled by the fidgeting of the man above, causing straw or dust falling on you or even the collapse of a bed board having become asquew and falling on you. I achieved top bunk status quite early, in fact I can't remember ever sleeping in a middle or bottom bed.

I can't remember other furniture but there were certainly some tables and chairs, as I can remember eating together with friends and playing chess across a table. I suppose the chess pieces and boards, like all "extras" had been bought from the Germans with cigarettes. Some were made by Russian prisoners; goodness know how, but certainly at the time we understood that this was the case, and probably the Russians sold them for food.

Red Cross Parcels were distributed, one per man, I believe about weekly but I am not sure that it was that frequently.They all contained various varieties of dried egg, margarine, milk powder and canned meat or fish, cheese, biscuits, and cigarettes. There were three kinds: British, Canadian and American. I, and I think most of us. preferred the Canadian, because they always contained a milk powder called "KLIM", which apart from making very good milk, was supplied in a large tin, invaluable to prisoners, as they could be used as drinking vessels. We became smart at furnishing handles for the KLIM cans. There always seemed to be a tin cutter and even pliers available to borrow, bought by cigs, of course.

Almost every one smoked, so the cigarettes, especially the British ones, were eagerly anticipated. I remember a friend of mine, on hearing that Red Cross Parcels had arrived, said with pleasure, "Hooray! We smoke again!" not "We eat again!" Non smokers had a fine source of currency!

When the fags arrived we all had to give one to the Man of Confidence to buy things for the common good in the hut. Cigarettes were the currency used among prisoners as well as in prisoner/guard transactions. For instance, in a camp that size there were many talented musicians, and from time to time we listened to them playing excellent jazz or solo violin etc, any small scale music in fact. We also had lectures from prisoners who had unusual or interesting jobs, from pro footballers to prison warders. One funeral director , a natural comedian, kept us in fits of laughter

with hilarious, but unrepeatable, tales about his sombre civvy job! There were also two impressive shows by hypnotists, one British and one Dutch. We might give them a few cigarettes for the entertainment.

After D-Day, as the second front advanced eastwards, Red Cross Parcels could not be delivered and we were hungry. Most of us were pretty cheerful though. Fortunately it was before the days of "counselling" and there was no sympathy for self pity. The best counselling is to be in the company of others in the same situation. We knew the war could not last much longer and hoped that we should be liberated by the Americans, but in fact one night the front passed through and at first light we saw four Russian Cossacks mounted on horseback and brandishing light machine guns. Eventually, having killed the few Germans still on the camp, they passed on, and we were left to manage as well as we could, living "off the land" for two or three weeks, sometimes getting food from Russian soldiers. I have heard that the Russians left us thousands of loaves of sour black bread, but I cannot remember anything about that.

Thousands of prisoners raided the stores for souvenirs, and it was difficult to get hold of anything. However I grabbed a few items, which were on display at my village's VE day celebration and exhibition. We lived "off the land" for two or three weeks sometimes getting help from soldiers in the long lines of Russian lorries taking supplies to the front. Some Russians once shot a pig and gave us some bits. Steve, a fellow prisoner and I tried to cook our bit, and took it to a cellar of an abandoned house to eat it, but it was burnt on the outside and raw in the middle. It did us no good at all as we were both very sick afterwards. It was dangerous to walk about the countryside, as there were likely to be both Russian and German soldiers all over the place in the chaos after the front had moved through. My friend Steve and I entered two or three houses, to see what

we could find. Of course the occupants had fled, and the Russians had been through the houses, taking away anything they wanted that could be carried, and smashing everything else. One day just a hundred yards away Steve and I watched two Russian soldiers demanding a German farm worker's horse, and when he argued, they threw him to the ground and kicked him savagely and went off with his horse. I was saddened and moved by the sight, yet I had recently played a part in dropping many tons of bombs on Berlin, causing a million times more horror and suffering than what I had just witnessed.

News went round that we should walk the seventeen or so miles to a place called Riesa. Many British prisoners did so. It was the right advice, as after a few days American trucks took us to Leipzig, from where we were flown home in Dakotas to Dunsfold airfield. After a bit they took us to Guildford station, and I heard the name of my home station announced, but, Oh No! We all had to go up to some RAF station, many

miles away north. The name I have quite forgotten. There we bathed and were fitted out with new uniforms.. We were questioned about that final operation, and about life in Stalag 4B, and had medical checks. Apart from being about a stone and a half thinner, there was nothing wrong with me, and I was pleased to find that I had become a Warrant Officer, with a uniform of finer material. and a somewhat larger pay-off for my pay during my stay as a prisoner.

I realised that for, me and Taffy , though not for poor Bob or the injured members of the crew, I was lucky to be shot down and escape, as if we had returned safely from that raid it was pretty certain we would eventually be shot down again and maybe all be killed. I had a few days earlier seen the Squadron Commander's record book, and just a few pages back, both crew lists on the left page and on the right, all four crews listed had big crosses drawn over them. That's how things were when Berlin was the target night after night. When I saw that book I knew that we were living in the valley of the shadow of death. However, our efforts were not really appreciated later, as no Campaign Medal was struck for Bomber Command crews. I did not want to join the Armistice Parades with no medals, when many of the marchers were adorned with half a dozen medals, so I

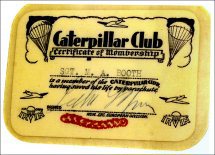

had to buy one offered by a firm that dealt in such things, and also I bought a commemorative PoW Medal. I wonder in how many other countries the veterans had to buy their medals. All I had was the tiny Caterpillar Club badge, a little gold badge given to all airmen who had saved their lives by parachute. The badge had red eyes for those shot down in flames, blue eyes if over the sea. It is shown in the accompanying photograph.

Of course the war with Japan was still on. I was on leave when they dropped the A-bomb. My mother wept tears when she read about it - not of sorrow or horror - but of joy, as she realised that her two sons would not have to go out to war again. Very soon, I pushed all this into the back of my mind for a while, as I had more important things to think about than a World War! . such as to decide how I was to earn a living, four years later than it might have been! Eventually, I became a schoolmaster and spent thirty six good years teaching in primary schools.