Policing in Brockham

by Bob Bartlett

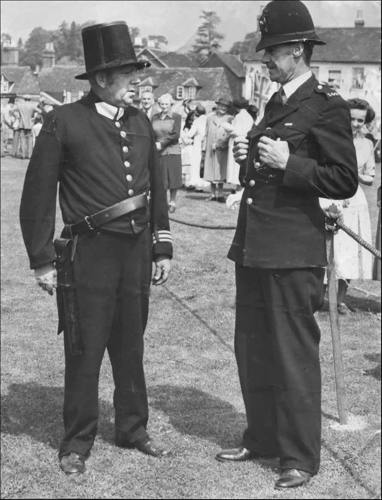

A constabulary duty to be done

When you think of a village policeman, you think of John Finch; large, carrying the signs of good living, avuncular, smiling, friendly. Not overworked, with time to stop and talk, to listen and to deal with those little quality of life issues that can make the difference to someone's life. If not on duty on his bike, he lived in the village and could be found at his house in Middle Street. His wife was a part of the team, with expectations from the local superintendent that she would play her part in the policing of the area John was responsible for. John was to serve for many years in Brockham, and was to die too soon after he retired. If there ever was a golden age of policing John Finch was a part of it. The hours were long and difficult, the duty frequently monotonous, the pay was appalling, but it was a good job to have, a way of life with an early pension. The public had a respect for the policeman, along with the vicar and the Doctor, although for some it may have been given grudgingly.

Every village has its share of the anti-social, those who are a pain in the neck to the rest of the community. The strange thing is that somebody always loves them!

At the time of Queen Victoria's death in 1901, the constable worked a basic 60 hours a week for 22s .9d, rising to 29s 2d when on the top rate. This works out at fewer than 5d an hour when bricklayers were being paid five and a half pence. There was no such thing as an annual pay round and the wages were the same 20 years on. Pay remained the same throughout the First World War, when many of the police officers were called up, with several being killed.

Things became so bad that the Metropolitan Police came out on strike, and there was a feeling of unrest in the Force, across the county. A local pay rise was awarded then soon after, a national rate of pay was agreed, along with a boot allowance of 1s 6d a week. John Finch was still receiving an allowance to buy his boots when he cycled the lanes of Brockham. Another allowance that started in 1925 and continued until modern times was the lamp allowance. This followed great disputes over the issue of electric or oil lamps for the patrolling constable.

It was not until 1910 that the law was changed to allow a policeman a day off. Yet there was delay in implementation and it was not until 1914 that it was adopted in Surrey. The day off could be cancelled if there was an emergency, and the officer had to rest and do nothing that would "militate against the object of the Act'. A local newspaper got hold of a copy of the order and said that "the order was impertinence - did the Chief Constable think that his officers would get drunk?"

To leave their beat, even on a day off the village constable had to seek permission from a senior officer. The war came and the day off was lost. Hard times

The policeman's wife was important, and her character had to be impeccable. In 1899 an order was issued that insisted that before a constable could marry, his application to the Chief Constable had to be "accompanied by a recommendation or testimonial from a clergyman, or some respectable person, who can guarantee the respectability of the woman who the constable intends to make his wife". Additional conditions were added soon after. A man had to have served four years before he could marry, or he had to have reached the age of twenty six years. The requirement to seek permission to marry, and the need to submit details of the future wife, continued until fairly recently.

The new fangled bicycles were seen by the Chief Constable as inhibiting contact between the police officer and his public. Zooming along on the cycle did not allow for all the correct attention to be paid. Sound familiar?

Constables made what were called conference points. This they did up until the late 1960s. Some will remember seeing the policeman standing by the telephone box for 10 minutes every hour. Here he stood waiting for the sergeant to meet him or, for the station to telephone with a job. Before there were call boxes, many conference points were at large houses. These points accounted for the size of the policeman's stomach, because they got to know and charmed the majority of the cooks and housemaids.

All this John would recognise as, nothing much changed in over a hundred years. When radios came, there was no need for conference points. However, the new radios were seen by the Chief Constable as a potential opportunity for the constable to skive and not cover his beat. Points ensured that they went to the furthest house. With a radio they could sit with their feet up. Points stayed for a while until the ridiculous nature of the order became apparent, and they were abandoned. At the time of the arrival of the radio, police cars became more abundant. In the early 1960s there was only one patrol car in the area, a Hillman Husky, a sergeant's car without a radio and the Criminal Investigation Department car, again without radio. There were also two Triumph Speed Twin 350 cc motorcycles. There was also the Traffic Department, based at Spital Heath in Dorking. The lack of mobility of the police was a reflection of the fact that few people had cars, and even fewer telephones. There were few emergency calls, but a great number of accidents. There was a time when the only transport was a horse and buggy for the superintendent. In these days, much attention was given to controlling the growth in road traffic.

Aggressive cyclists occupied the police in the early 1900s, soon to be followed by "motorphoba", with the Chief Constable stating that "I will stop them at any cost'. The Daily Mail reported that "It needs more than 12 miles per hour to make a good breeze. So a pretty contest is being pursued in Surrey between the police and the automobilists. The latter are becoming very indignant, because they say the police are not playing the game in a sportsmanlike way".

The Chief Constable wanted every vehicle to display a number but the automobolists were against this as of course they could then be traced. Reigate came top of the list for the greatest numbers of motorists captured. The emphasis was on reducing speed, and protecting those that lived in villages from the car and cycles who placed people at risk. Does this sound very familiar? This was certainly a battle that had to be fought and one that has been lost.

The future Prime Minister Lloyd George lived in the Dorking Division and in 1913 the Suffragettes set off a 7 lb. nail bomb at his house that was being built at Walton on the Hill. Emily Pankhurst was arrested for this offence. There were other bombings within the county left by the Suffragettes - nail bombs to start the century and nail bombs in London at the end.

In 1926 during the General Strike officers from the Surrey Constabulary, including local men, were sent to the pits in Derbyshire, and were very unhappy about their food and accommodation. Sixty years on, the Surrey Constabulary were sent to the pits in Derbyshire, and were unhappy about their food and accommodation, but now they had overtime payments. Many a boat called the "Flying Piquet" and car named "Arthur" was purchased on the back of the overtime payments.

The Second World War brought many additional duties. There were the War Reserve Constables that were taken on, and the Special Constabulary, to help with the work and to replace the young men called to the Colours. There also appeared the Women's Auxiliary Police Corps, with the first women officers in Surrey. The soldiers and airmen stationed across the county attracted a number of young, and not so young, ladies and some that were not strictly ladies. This was a constant cause of concern and work for the police. One camp follower was to be murdered and buried by a Cree Indian member of the Canadian Army on Hankley Common. The police would have been heavily involved in the aftermath of the terrible bombings in Nutwood Avenue during the Second World War

In any potted history of an organisation such as the police much has to be left out. There is no central depository of historical documents to be consulted and anything that has survived is mostly by chance. However, in modem times memories allow for a few cases to be recalled that affect the village.

A few Personal Recollections about policing in Brockham:

Bill Bowry: At one stage the village police house was in Oakdene Road before the police house was bought in Middle Street at the junction with Oakdene Road.

Alec Overton: Mr Bleach was the Village Policeman. He called to the house once when Mum and Dad were plucking pheasants. They were quickly hidden under the table; but there were feathers everywhere. When he was leaving he said "he wouldn't mind a brace next time he called!"

Bill Bowry: In about 1940/1941 before I was called up PC Jim Bleach was badly beaten by Canadian Soldiers at the Barley Mow Pub. He was never quite the same after that.

Robert Bartlett, former chief superintendent, Surrey Police